Finding The Dominant On The Guitar Neck

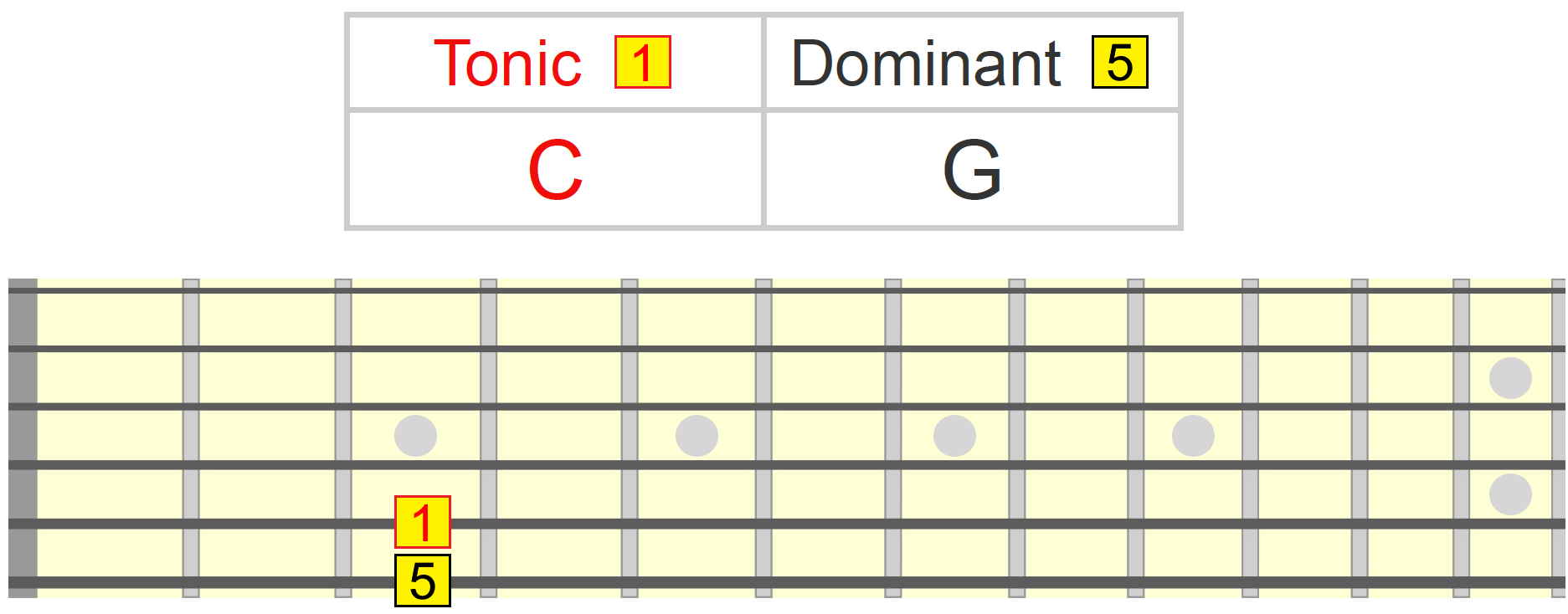

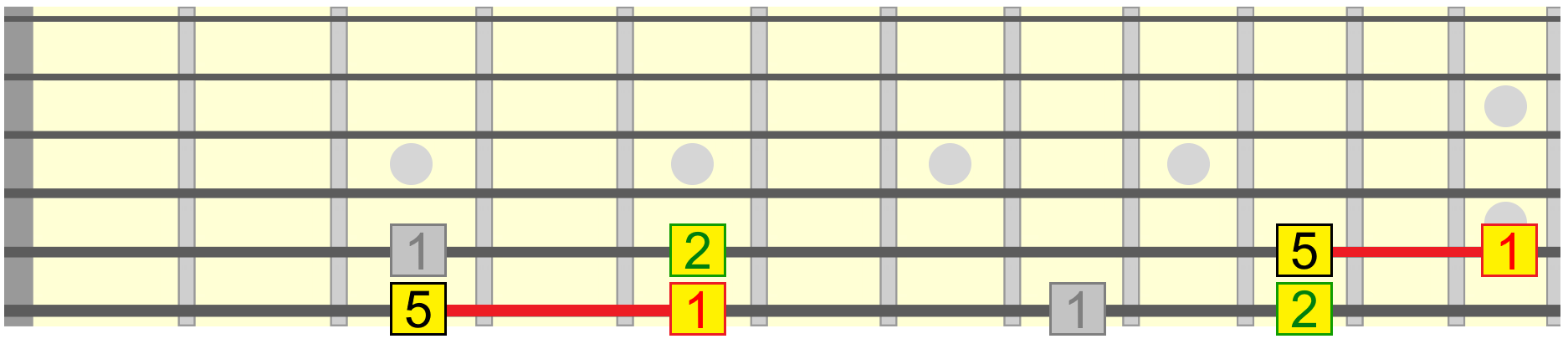

First, let's recap on how we can find the dominant of any key on the neck.

Let's say we were in the key of C major or minor. We might find the tonic root of C on the 5th string at the 3rd fret.

The dominant root can be found on the same fret on the 6th string, directly below the tonic...

This is the equivalent of a perfect 5th interval, and the degree on which the dominant or 5 chord (often written using the numeral V) naturally resides. Therefore, in the key of C (major or minor) G would be our dominant root...

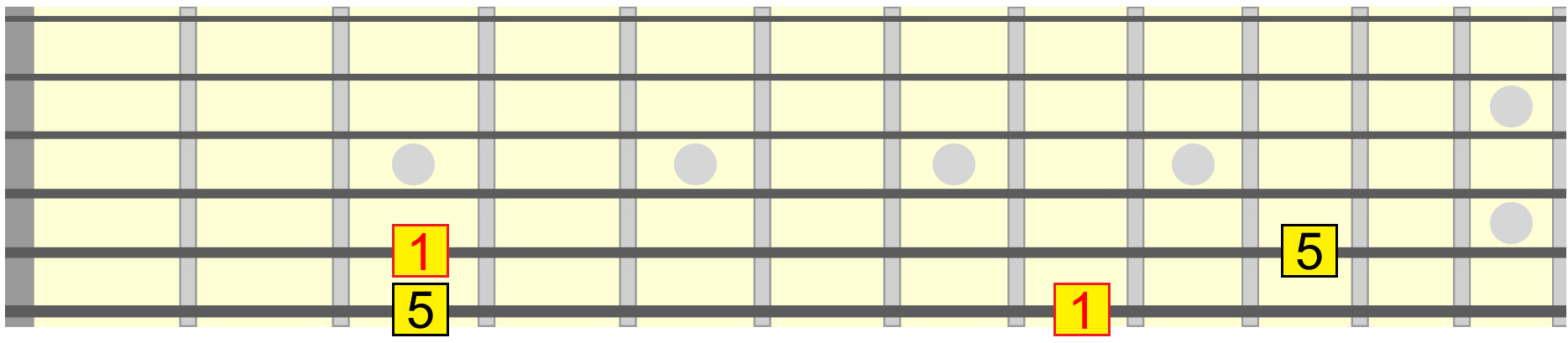

Or, we might find the root of C on the 6th string, at the 8th fret. In relation to this position, the dominant root would lie two frets up on the 5th string...

We can of course apply this tonic-dominant root relationship to any key. Familiarise yourself with the sound of this relationship as it occurs frequently in music.

Dominant Based Key Changes

Now, this tonic-dominant relationship can be used to help us move more naturally into a new key.

The first method of this we're going to look at demonstrates the powerful function of the dominant, as we can use it to transition into distantly related keys.

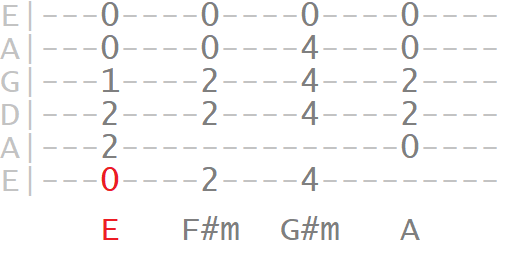

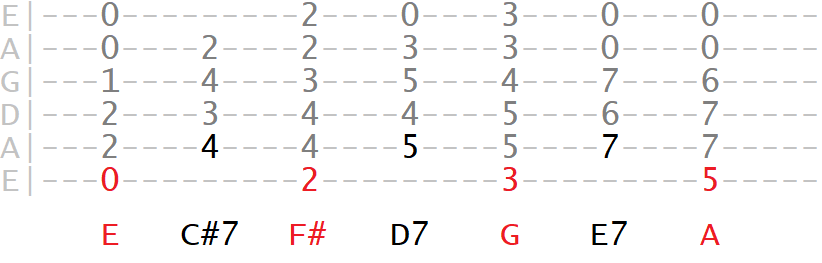

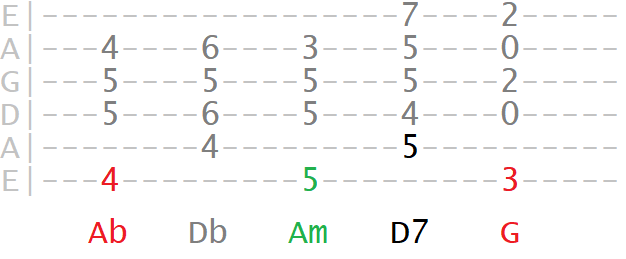

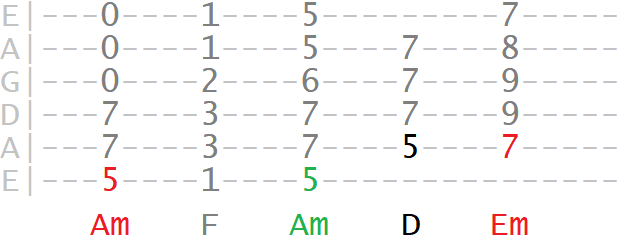

Here I'm playing a simple E major key progression...

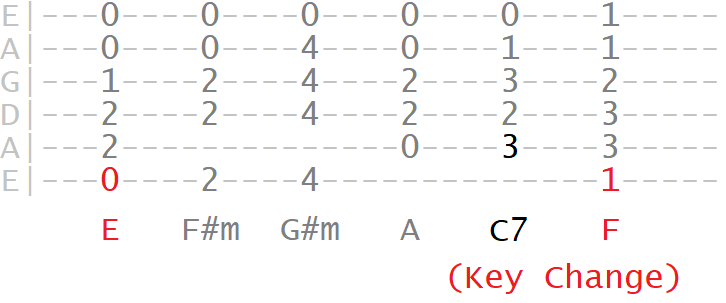

Now I'm going to make a key change to F major, which is considered a distant key to E major. However, by finding the dominant of F major, which is C, and building a dominant 7th chord on that degree, we can signpost the way more purposefully into our new key...

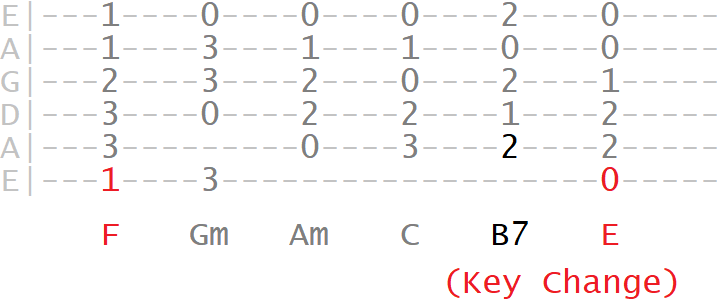

Now it's up to you where you go with this new key. But if we wanted to eventually move back into E major, we can simply use the same dominant signpost to direct us back, with B7 being the dominant of E major...

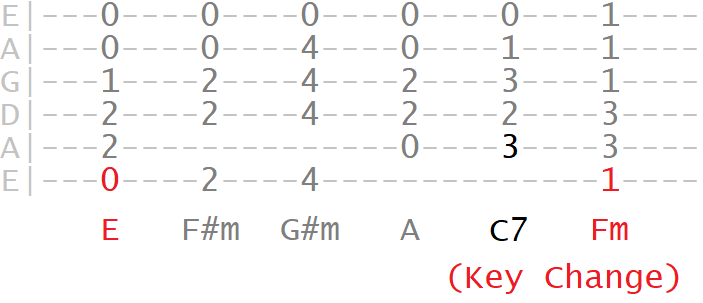

We could also use the dominant of F, C7, to move into the key of F minor, as it functions in a similar way, setting a completely new mood for the piece...

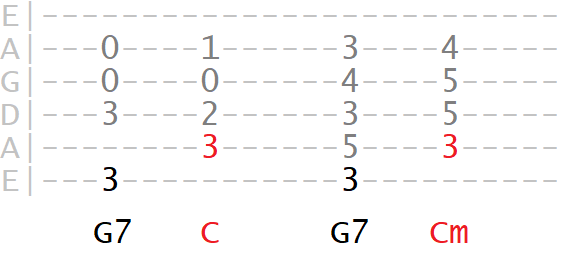

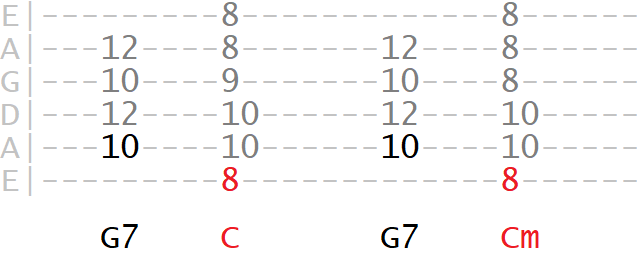

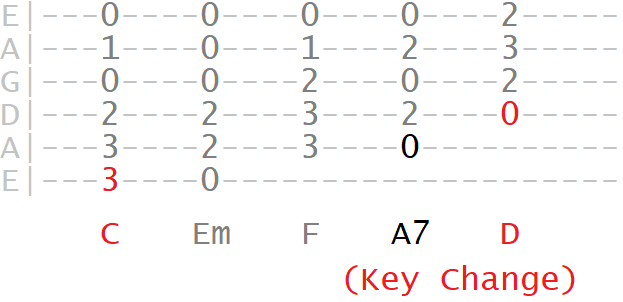

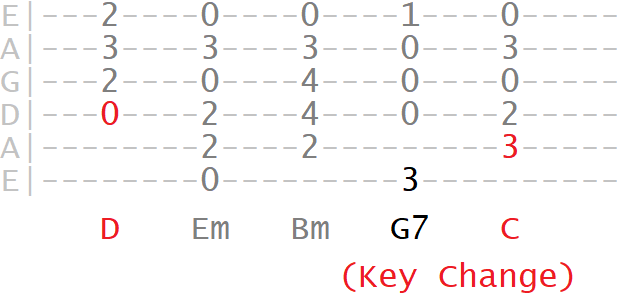

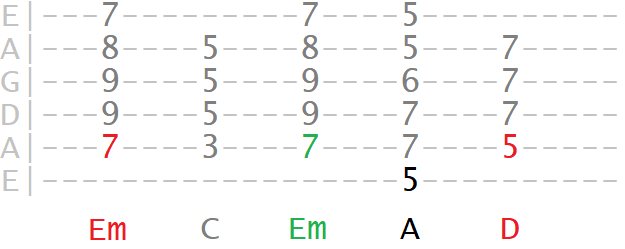

Another example, starting in the key of C major...

There we used A7 as the dominant of our destination key, D major.

And back to C major, using its dominant of G...

We could even modulate through multiple dominants and tonics before we land in our destination key...

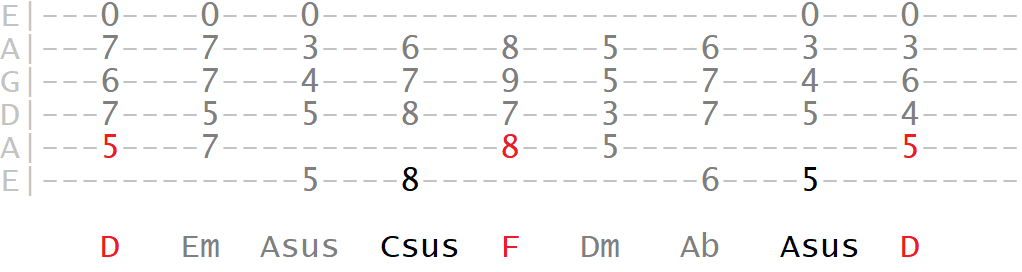

Remember we can also use suspended chords in the dominant position. These can also help us to move more smoothly into distant keys...

A good rule of thumb is, if your key change sounds too disjointed, try introducing the dominant of the destination key just before the change to help prepare it.

4 5 1 Key Changes

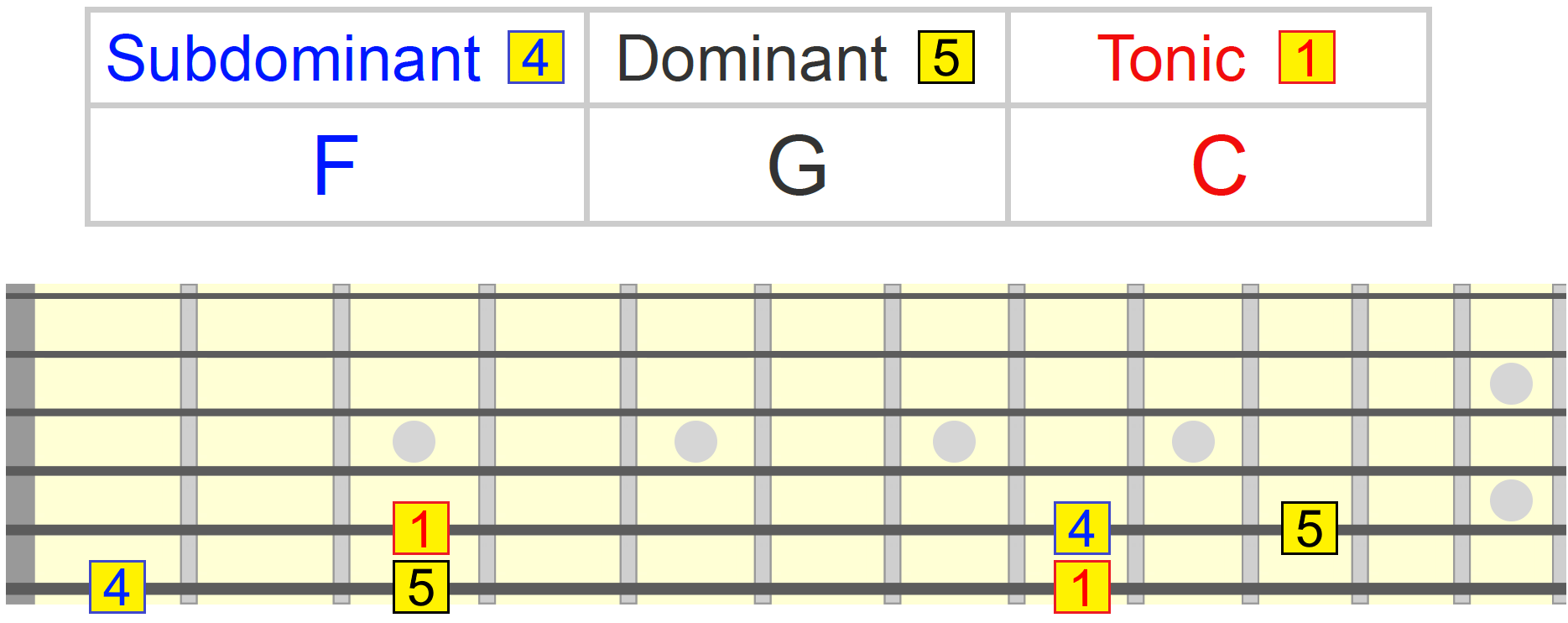

The dominant can also be supported by the subdominant or 4 (IV) chord in preparing key changes, giving us a 4 5 1 resolution.

The subdominant root can be seen as lying two frets down from the dominant root on the same string. Therefore in the key of C, for example, F would be our subdominant and G our dominant...

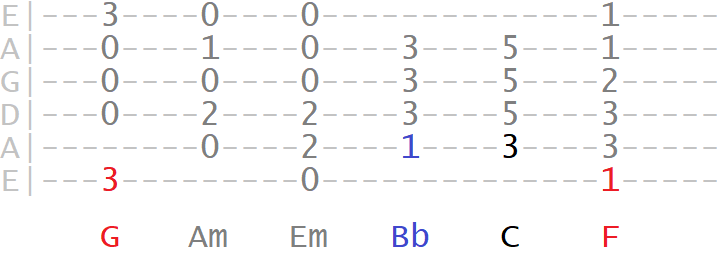

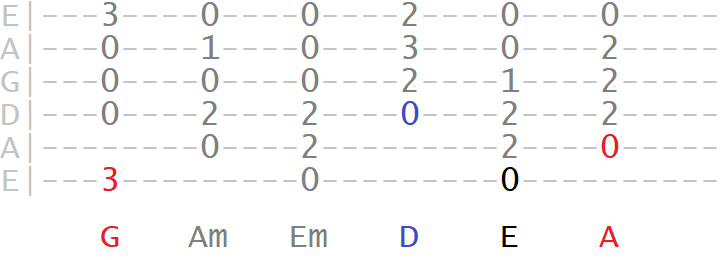

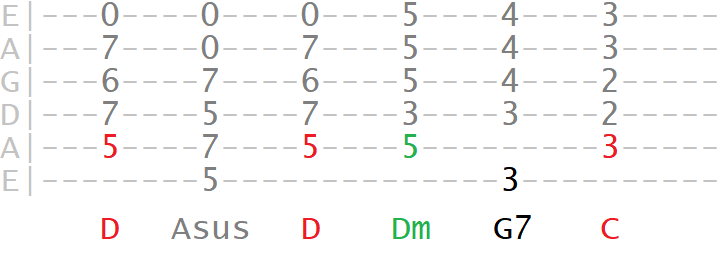

In the key of G major, we could change to the key of F major by playing through that new key's subdominant and dominant, B♭ major and C major respectively...

Or, to A major, by using A major's 4 and 5 of D major and E major...

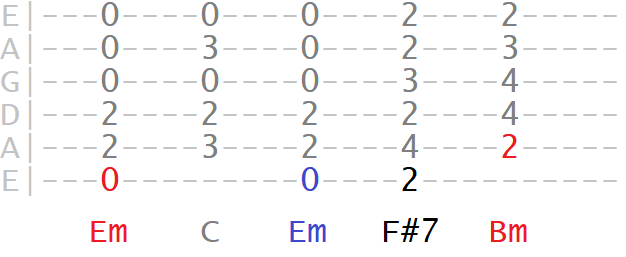

And we can do a similar thing with minor key changes. Typically, you'll hear the tonic minor chord become the subdominant of the new key.

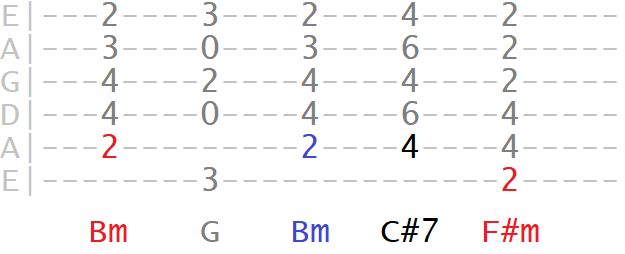

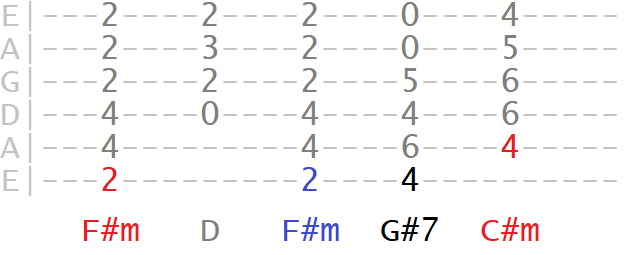

For example, Em becomes the 4 of Bm...

Bm becomes the 4 of F♯m...

F♯m becomes the 4 of C♯m...

2 5 1 Key Changes

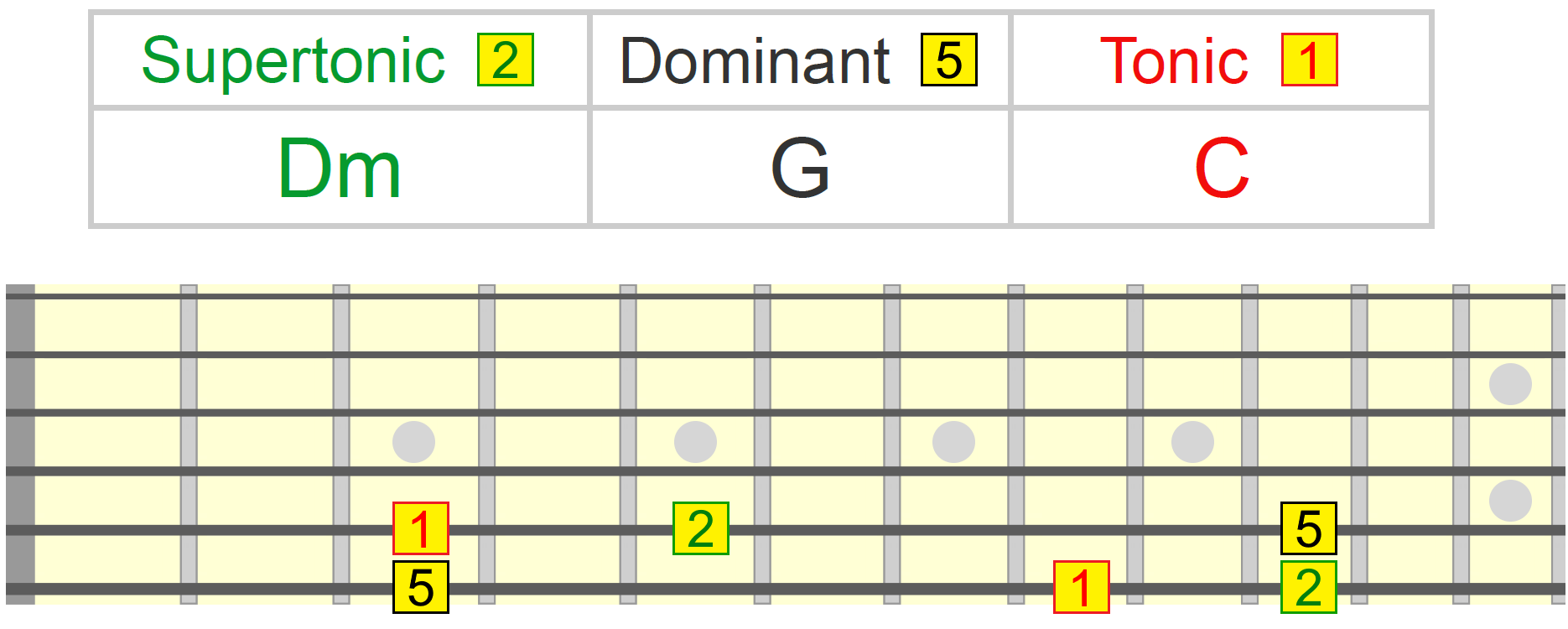

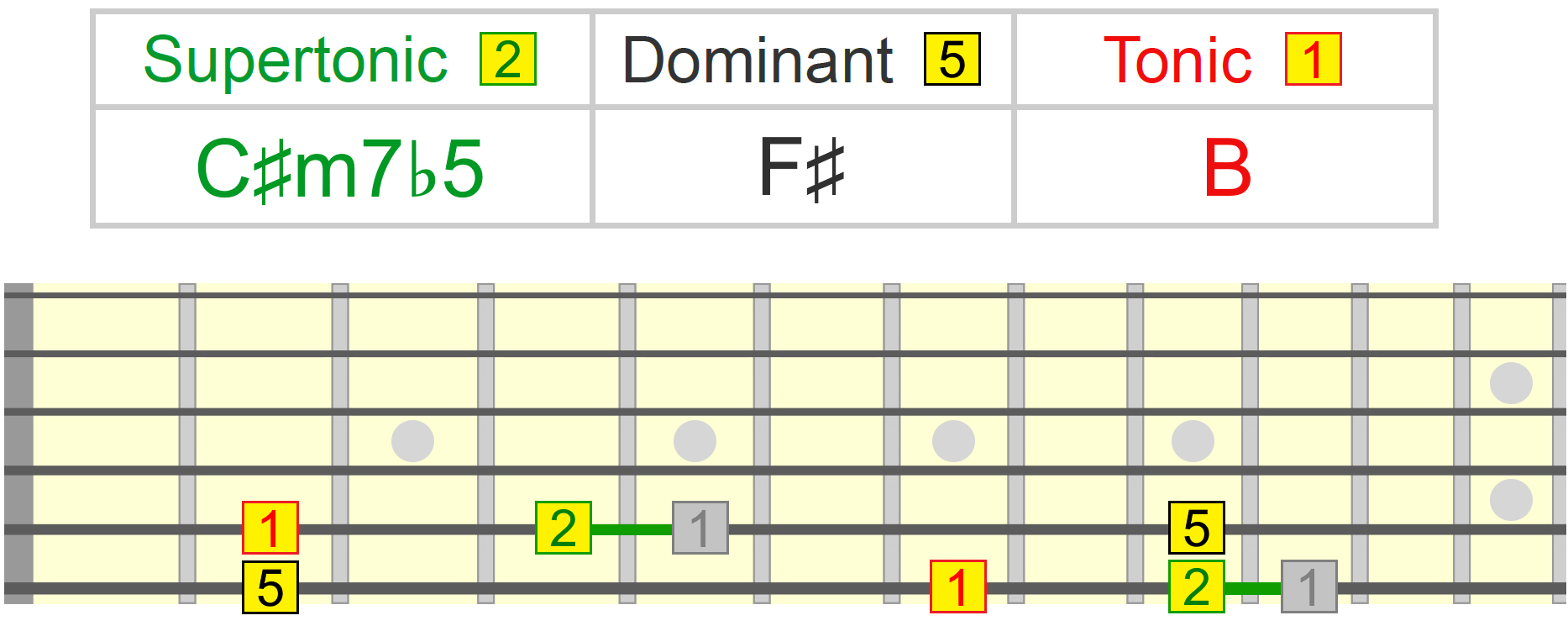

Similar to the 4 5 1 key change, we can also use the 2 (ii) chord, also known as the supertonic and typically a minor chord, to lead us through a dominant based key change.

The 2 chord root can be found in the following positions in relation to the tonic and dominant - two frets up from the tonic root is an easy way to visualise it...

2 5 1 is a very common turnaround in jazz music and a very natural way to modulate to new keys.

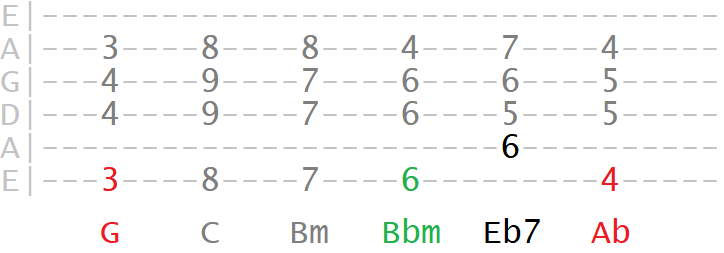

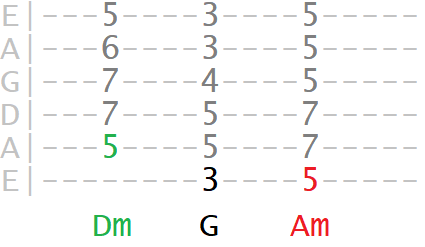

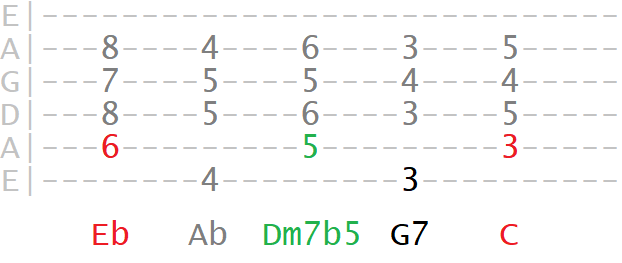

Take this chromatic key change from G major to A♭ major. We could use the 2 and 5 of A♭ major to move into our new key...

And back into G major using its 2 and 5...

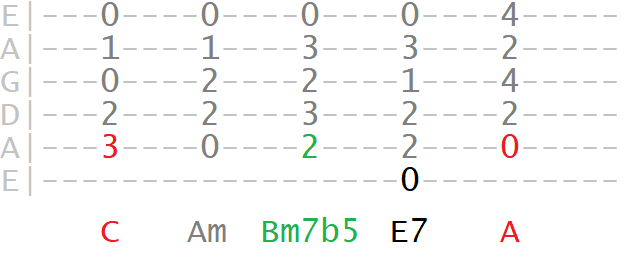

We can even make a parallel change from major to minor tonic and use that minor chord as the 2 of the destination key...

Sometimes we might want to resolve our 2 5 to the relative minor tonic of the new key. This can be seen as two frets up from the 5...

Here, instead of resolving our 2 5 to C major, we resolve up to its relative A minor...

And if you're on a minor tonic, that can become the 2 chord that links to the 5, giving us a path into a new key, whether major or minor.

Here, instead of resolving our 2 5 to G major, we resolve up to its relative E minor...

And here we turn the E minor tonic into the 2, leading through the 5 to a new key of D major...

We can also use the natural 7th degree chord as part of a 2 5 1 key change.

Let's say we started in the key of D major. We might move down one fret to the key's 7th degree chord. This then becomes the 2 of the destination key...

We'd typically build a "half diminished" seventh chord on that new 2nd degree, also called a m7♭5 chord.

An example starting in E♭ major, moving into C major...

And from C major into A major...

Remember that in all of these examples, we can move into a minor tonic as well as major.

Summary

Key changes, when used consciously and purposefully, can really take your songs in a new direction, maybe give the chorus a lift or create whole new sections in a piece.

If we want to mix the mood of a song, we can start in major and move into minor or vice versa, using a straight dominant link to the new key, or utilising 4 5 1 or 2 5 1 to better help "prepare" the transition for the listener.

Overall I hope this lesson has opened your eyes and ears to many new songwriting possibilities!