Home

> Progressions

> I and V chords

We're first going to look closely at the dominant chord, its

function and

its relationship with the tonic - a relationship that will be integral

to

many of the chord progressions you play.

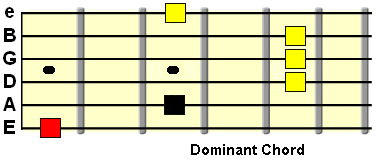

Dominant chords are an important part of music theory in general, not just on guitar. I won't spend time on what the name "dominant" means, as it's not important what you call it, rather you understand its musical function.

When thinking about and writing your own chord progressions (a sequence of chords), dominant chords can be seen as natural tension chords before returning back to the starting chord of the progression.

By "tension" I mean they have a naturally unresolved feel to them, leaving the chord progression feeling "away from home". So, first, think of dominant chords in relation to a journey away from that starting 1 chord.

Let's say we begin a chord progression on C major. We can call that the tonic chord or the 1 chord. That is "home". During the progression, we journey "away from home" using other chords. Some progressions spend very little time away from the tonic and stay close to home. Others go on a longer journey. However, the dominant (or 5) chord, can be used, in both long and short journeys, as a natural gateway to return back home/resolve to the tonic chord.

It's this resolution that helps to reaffirm the major key centre. Not always the aim in music, but used enough to know about.

Take a listen below to a tonic major chord followed by its relative dominant chord, before returning back to the tonic.

Click to hear

In that example, our tonic chord was C major. The dominant chord was G major. However, the relationship between tonic and dominant chords is the same no matter which key you play in. Take a listen to this same tonic-dominant relationship but in incremental keys:

Click to hear

...and so on and so forth. When the tonic chord changes, the dominant chord moves with it as a relative position...

For the moment, it's good to train your ear to the sound of that relationship and the tension of the dominant chord before its return home.

To add to that tension, the dominant chord is often played with a flat 7th interval. Don't worry if you're not sure what that means yet. All will become clear. We'll look more at this particular variation next time.

Let's delve a bit more into the theory and function of this chord...

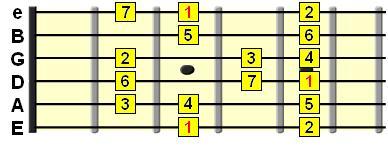

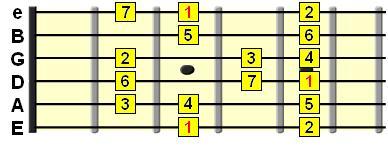

Let's take a typical "boxed" major scale pattern:

As you may already know, that pattern can be moved up or down the fretboard, depending on which key you're playing the major scale in. But let's say we're in the key of G, as rooted on the 3rd fret above.

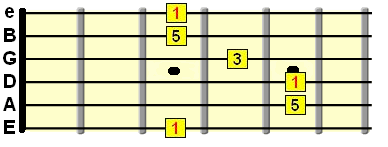

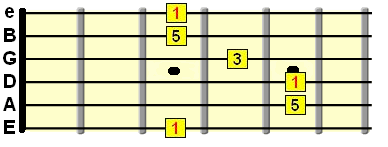

We could build a tonic major chord over that major scale shape by simply using an E shape barre:

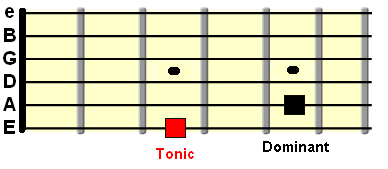

So there's our tonic "home" chord - G major. Now, the dominant chord of that same key is rooted on the 5th degree of the same root major scale. Identify the 5th (5) note on the tonic above. That is where the root note of our dominant chord will sit...

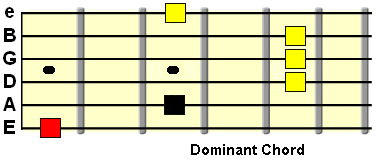

We can then build the dominant major chord from that dominant root note. I've used the A shape barre chord in the example below, because its lowest root note lies conveniently on the A string...

Incidentally, in this example, because the tonic chord was G major, the dominant chord is D major. Let's listen to that tonic-dominant relationship again, this time between G and D major:

Click to hear

To really hear the dominant function in its element, we need to add some chords away from the tonic, and use the dominant chord as the final chord before returning home. A common 3 chord progression is: I ii V, which is Roman numerals for: 1 (tonic or 1st degree chord) 2 (2nd degree chord in major scale) and 5 (5th degree chord).

Click to hear

However, any chords you might use away from the tonic (as long as you think they're musical) can interact with the dominant chord in this way.

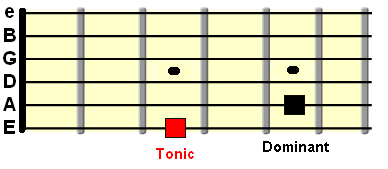

Now, this tonic-dominant root note relationship can also be identified in other positions where chord root notes occur (e.g. for the common barre shapes)...

Remember, all these positions are the relative positions between tonic and dominant, the same as root (1) and 5th (5) intervals from the major scale. The actual fret positions are not important, as these are movable relationships. Tonic moves, dominant moves with it, just like a movable chord shape or scale pattern. Starting with the one we already know...

So as these are root note intervals, we can build chords on each of them - tonic chords and dominant chords on their respective root note positions. This is just to give you a visual reference to get your bearings on the fretboard. Once you know the root notes, you can build the actual chords wherever you want, using other chord shapes you've learned.

So, in a nutshell, the dominant chord root note is on the 5th degree of the tonic's major scale, the tonic being the 1st degree of that same scale. It's this tonic chord which defines the key of our progression. For example, if the tonic were C major, our progression would be said to be "in the key of C major", and the root of our major scale would be C (useful to know for soloing).

That, in its basic form, is the I - V (or 1 - 5) relationship. Most songs, especially pop songs you'll hear will make use of this relationship in some way.

But of course, there's more to it than what we've covered here. In the next lesson, we'll delve further into the theory behind dominant chords and how you can make really effective use of them in your songwriting, especially by using what's called the subdominant (or 4 chord)

I hope this has, at least partially, opened a new door for you as far as guitar theory goes. Perhaps I've bored you to death in the process. If so, perhaps more interactive learning will bring you back to life.

Dominant Variation in Chord Progressions

Main Guitar Chord Progressions Section

Tonic & Dominant in Chord Progressions

The tonic (I or "1 chord") and dominant (V or "5 chord") are probably the most important chord relationship used in chord progressions.

|

Dominant chords are an important part of music theory in general, not just on guitar. I won't spend time on what the name "dominant" means, as it's not important what you call it, rather you understand its musical function.

When thinking about and writing your own chord progressions (a sequence of chords), dominant chords can be seen as natural tension chords before returning back to the starting chord of the progression.

By "tension" I mean they have a naturally unresolved feel to them, leaving the chord progression feeling "away from home". So, first, think of dominant chords in relation to a journey away from that starting 1 chord.

Let's say we begin a chord progression on C major. We can call that the tonic chord or the 1 chord. That is "home". During the progression, we journey "away from home" using other chords. Some progressions spend very little time away from the tonic and stay close to home. Others go on a longer journey. However, the dominant (or 5) chord, can be used, in both long and short journeys, as a natural gateway to return back home/resolve to the tonic chord.

It's this resolution that helps to reaffirm the major key centre. Not always the aim in music, but used enough to know about.

Take a listen below to a tonic major chord followed by its relative dominant chord, before returning back to the tonic.

Click to hear

In that example, our tonic chord was C major. The dominant chord was G major. However, the relationship between tonic and dominant chords is the same no matter which key you play in. Take a listen to this same tonic-dominant relationship but in incremental keys:

Click to hear

...and so on and so forth. When the tonic chord changes, the dominant chord moves with it as a relative position...

| Tonic (I) | Cmaj | Dmaj | Emaj | Fmaj | Gmaj | Amaj | Bmaj |

| Dominant (V) | Gmaj | Amaj | Bmaj | Cmaj | Dmaj | Emaj | F#maj |

For the moment, it's good to train your ear to the sound of that relationship and the tension of the dominant chord before its return home.

To add to that tension, the dominant chord is often played with a flat 7th interval. Don't worry if you're not sure what that means yet. All will become clear. We'll look more at this particular variation next time.

Let's delve a bit more into the theory and function of this chord...

Dominant chords and the major scale

It's surprising just how much music theory stems from knowledge of the major scale. Dominant chords are no exception. This will explain why we call it the "5 chord"...Let's take a typical "boxed" major scale pattern:

As you may already know, that pattern can be moved up or down the fretboard, depending on which key you're playing the major scale in. But let's say we're in the key of G, as rooted on the 3rd fret above.

We could build a tonic major chord over that major scale shape by simply using an E shape barre:

So there's our tonic "home" chord - G major. Now, the dominant chord of that same key is rooted on the 5th degree of the same root major scale. Identify the 5th (5) note on the tonic above. That is where the root note of our dominant chord will sit...

We can then build the dominant major chord from that dominant root note. I've used the A shape barre chord in the example below, because its lowest root note lies conveniently on the A string...

Incidentally, in this example, because the tonic chord was G major, the dominant chord is D major. Let's listen to that tonic-dominant relationship again, this time between G and D major:

Click to hear

To really hear the dominant function in its element, we need to add some chords away from the tonic, and use the dominant chord as the final chord before returning home. A common 3 chord progression is: I ii V, which is Roman numerals for: 1 (tonic or 1st degree chord) 2 (2nd degree chord in major scale) and 5 (5th degree chord).

Click to hear

However, any chords you might use away from the tonic (as long as you think they're musical) can interact with the dominant chord in this way.

Now, this tonic-dominant root note relationship can also be identified in other positions where chord root notes occur (e.g. for the common barre shapes)...

Remember, all these positions are the relative positions between tonic and dominant, the same as root (1) and 5th (5) intervals from the major scale. The actual fret positions are not important, as these are movable relationships. Tonic moves, dominant moves with it, just like a movable chord shape or scale pattern. Starting with the one we already know...

So as these are root note intervals, we can build chords on each of them - tonic chords and dominant chords on their respective root note positions. This is just to give you a visual reference to get your bearings on the fretboard. Once you know the root notes, you can build the actual chords wherever you want, using other chord shapes you've learned.

So, in a nutshell, the dominant chord root note is on the 5th degree of the tonic's major scale, the tonic being the 1st degree of that same scale. It's this tonic chord which defines the key of our progression. For example, if the tonic were C major, our progression would be said to be "in the key of C major", and the root of our major scale would be C (useful to know for soloing).

That, in its basic form, is the I - V (or 1 - 5) relationship. Most songs, especially pop songs you'll hear will make use of this relationship in some way.

But of course, there's more to it than what we've covered here. In the next lesson, we'll delve further into the theory behind dominant chords and how you can make really effective use of them in your songwriting, especially by using what's called the subdominant (or 4 chord)

I hope this has, at least partially, opened a new door for you as far as guitar theory goes. Perhaps I've bored you to death in the process. If so, perhaps more interactive learning will bring you back to life.

Was this lesson helpful? Please let others know, cheers...

| |

Tweet |

Stay updated and learn more

Sign up to the newsletter for updates and grab your free Uncommon Chords book

Sign up to the newsletter for updates and grab your free Uncommon Chords book

Related

Dominant Variation in Chord Progressions

Main Guitar Chord Progressions Section