Transcript

Getting up to speed with a lick, riff, phrase, sequence, whatever you wish to call it, is often a cause of frustration for many guitarists. A lot of us experience that phenomenon of "hitting a brick wall".

While the goal is not necessarily to play as fast as possible, for most of us there is a goal to play as cleanly and gracefully as possible at a desired tempo, which could involve 16th notes north of 100 BPM (beats per minute), for example.

It involves fractions of seconds of co-ordination between fret hand and pick hand. But as we know, on those movements we are able to repeat with a very narrow margin of error, it becomes close to automatic.

This is known as muscle memory - where what initially required a good deal of conscious attention and physical effort becomes more sub-conscious and deferred to a refined, grooved out pathway between our motor neurons and nerve endings.

Even when improvising in the moment, musicians tend to be drawn to pre-rehearsed movements that have already been embedded in their muscle memory. It's their "bag of tricks".

Repetition & Muscle Memory

So what is the most efficient way to develop this muscle memory? Repetition is obviously the primary element. We have to repeat a movement so many times before that feeling of conscious effort takes more of a back seat, and we can focus more on harmonic and melodic context and the placement of related patterns and shapes on the neck.

But even this very simple concept of repetition can give rise to obstacles, some of which we may be creating unnecessarily for ourselves.

One of those obstacles is created by the inadvertent tendency to repeat mistakes at too high a tempo, too many times, often out of the belief that, if we just repeat a challenging passage enough, we'll gradually iron out the kinks.

However, more often than not, all that will happen is we'll develop a kind of competing muscle memory around those repeated mistakes. Remember that your motor system doesn't care if you're playing clean or sloppy. It's the repetition of movement and exertion of muscle that creates the "memory".

Even at best, if we're making a bunch of different mistakes in different places each time around, the inconsistency will interrupt the development of the muscle memory we do want.

So what we're ultimately striving for is consistently clean repetition. Where we can pick up the guitar and plow straight into something without a second thought and with minimal mistakes. The only way to ensure we can maintain progress with this is to first find a tempo at which we can play whatever it is we're working on as close to flawlessly as humanly possible.

Of course, mistakes and slight stumbles in timing are unavoidable, even at slower tempos. Even the greats slip up occasionally. Such hiccups are always forgiven or overlooked, as long as they are infrequent and don't spoil the overall technical grace and sentiment of the performance.

The point is, if you notice you're making the same mistake several times around, or there's a consistent scattering of different mistakes, you're probably trying to move too fast, for now at least. We often need to slow down to figure out if it's a technique issue that needs correcting, or if it's simply that we're jumping ahead of ourselves with the tempo.

Impatience = Frustration

A lot of this jumping ahead of our current ability is down to impatience. If you've ever watched the video aptly entitled The Angriest Guitarist in the World...

Part 1

Part 2 (if that wasn't enough)

...you'll see how an absolute determination to play cleanly (which is wholly respectable), yet at the same time trying to maintain the tempo at which repetitive mistakes are happening, can lead to heightened cortisol levels and... smashed guitars.

But I genuinely don't believe those outbursts of visceral frustration were just for the camera. I know because I've rather embarrassingly been there, cursing at my own fingers for not doing what I want them to do (albeit not quite as emphatically as the guy in the video).

Give Yourself a (changeable) Beat

Now, the metronome might not be the most exciting companion to practice with. And if you feel a growing sense of monotony after ten minutes of repeating the same phrase to blips or ticks, then there are other ways to set the tempo.

This could be through drum tracks (links below) or, if you have a backing track or song, using software that allows you to change the tempo without having to change key.

But having a changeable tempo, a beat, no matter what it sounds like, is crucial to relieving us of much of the aforementioned frustration and breaking through that BPM barrier.

Drum Tracks & Tools I Use

Below are two of my favourite Youtube channels for drum tracks in various styles and at varying tempos. A great alternative to (or occasional respite from) the solitary blips and ticks of a metronome...

I've also been using a program called Song Surgeon (affiliate link) for many years to slow down tracks/songs, change key, remove vocals and many other useful manipulations. It's a very powerful tool for learning musicians (that would be all of us, right?).

However we set the tempo, it's important that we go back to basics and find a tempo whereby we can play flawlessly, or at least as flawlessly as humanly possible.

Don't be disheartened if it feels drudgingly slow, because following the process I'm about to describe will actually increase confidence and efficiency and decrease the time it takes to develop that consistently clean repetition at the desired tempo. Kind of like the tortoise winning the race against the hare. We also have to be able to walk before we can run - another example of the development of muscle memory. The process doesn't change.

Finding The "Breaking Point"

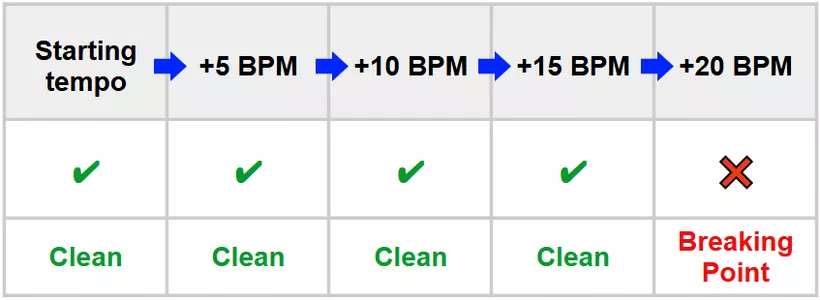

Choosing that starting tempo can be a little arbitrary. But, more importantly, there is a way to find what I call the "breaking point". This is the tempo at which things start to fall apart, mistakes start to be consistently made and we're suddenly playing catch up, yet below the desired tempo.

To find this breaking point, we're going to use increments of 5 BPM, starting from a comfortably slow tempo, until we hit it.

Why 5? Because it's small enough that we won't jump ahead of ourselves too much, yet large enough to make efficient progress. We can of course use smaller increments if necessary, to lazer target that breaking point. But I've found increments of 5 BPM will at least get us close enough and quickly enough, from a comfortable starting tempo, and not test our patience too much.

Again, there's some subjective judgement involved here but, once you feel you've hit that breaking point, where consistent mistakes are being made, the crucial thing is to step back 5 BPM as soon as you're confident you've reached it.

Contrary to how a lot of musicians might be compelled, it's the highest tempo at which we can play pretty much flawlessly that we should be spending the most time on in terms of repetition.

The reason this seems counterintuitive is because, if we can already play well at that tempo, why keep practicing it? Why not push for the more challenging tempo?

Well, for the simple reasons stated earlier. You don't want to over-rehearse mistakes. You don't want to throw inconsistency into the development of muscle memory and co-ordination skills. Your brain and fingers need some time with this more comfortable tempo to burn that template into memory.

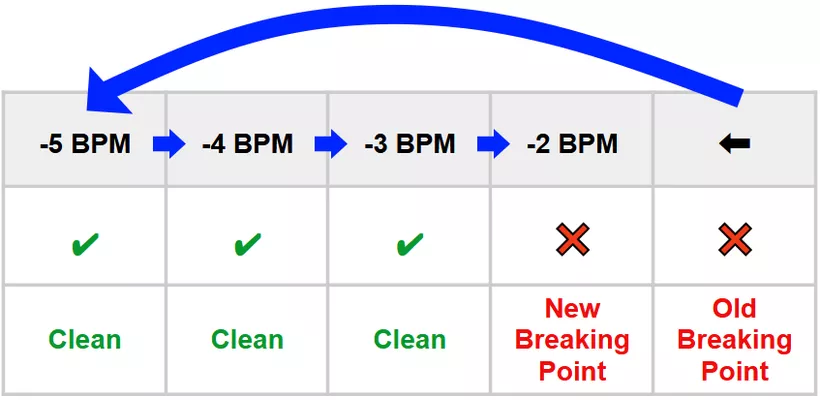

Once you step back from the "breaking point" by 5 BPM, you'll want to confirm you can indeed play consistently cleanly at that tempo. If so, this is where you can edge more towards that breaking point, perhaps using 1 or 2 BPM.

While this may seem like a very meticulous process, it does avoid the mistake of jumping too far ahead of ourselves, getting frustrated, feeling inadequate etc.

As it happens, muscle memory develops most in our favour in the place we can play most confidently. That is, if below the desired tempo, the highest tempo at which we can play well.

It may take several sessions of repetition at this fallback tempo to find that mistakes are becoming more sparse at the higher breaking point when we repeat test it. Eventually the old breaking point will become a new repetition point and a raised bar of confidence.

To avoid burnout, we can limit our repetition time to 10 or 15 minutes, play something else for a half hour, come back for another 10 minutes, more if you feel motivated enough. Breaking up the more intensive, repetitive drills with more explorative playing is a good rule of thumb for practice.

It may be you come back to it a day later and find there's a new breaking point, even below the initial one. Again, try not to get frustrated and stick to the process. Roll back the BPM until you can play well and you might find it was just a temporary lapse (we all have days where we need that extra warmup time).

The key takeaway here is to avoid rehearsing mistakes, which could include missed notes. It sounds so obvious, but so many of us find it difficult to resist the challenge of standing at that invisible wall and trying to break through it with sheer determination alone.

But guitar playing is not so much about brute force determination. It's about very subtle techniques that are occurring in the most nimbly jointed parts of our body. Most of the time that wall will remain until you come back to it with deeper muscle memory, forged at a comfortable tempo.

Other Things to Consider

Now, although this process, if persisted with, will work for most, there are other things to consider that can help us at the higher tempos.

Again, it's back to basics, and I'm aware that there is a reluctance to change what you may have become accustomed to over the years. Things like pick gauge, pick size, pick hand position, fret hand thumb position etc.

Pick Size & Shape

I'm by no means the quickest player on the planet. But about ten or so years into my playing journey, after trying numerous different picks, I came across the Dunlop M3. This was a much smaller pick than I had ever tried.

The smaller surface area meant my pick hand fingers were closer to the strings. The nub of the pick was less exposed and, as a result, I noticed playing became a little more effortless. I won't say it was some kind of magic bullet (or magic pick), but there was noticeably more technical comfort with how it felt between my fingers.

This is all very subjective, and we can't get away from that. But it does show that seemingly small changes can agree more with how our hands, fingers and their joints are constructed.

We're all different, down to very subtle degrees. And guitar playing is a subtle, technical art, even if big brash sounds are being made. So we shouldn't rule out experimenting with small changes like this.

Pick Gauge

(worked for Brian)

(worked for Brian)Pick gauge or thickness is another potential game changer. Most lead players prefer thicker picks, typically over 1mm, mostly for the improved tone - they can "dig in" more and attack the strings using the solidity of the pick as support.

Brian May famously even uses an old sixpence coin. But you may find the additional flex of a lighter pick, that is under 1mm, helps you to glide more over the strings.

For several years I played in a funk band, and those lighter picks really helped to create some intricate 16th note rhythms with chord playing, albeit with a minor sacrifice in tone when it came to a lead part.

So you may find there is some compromise to accept between speed and tone.

Pick Angle

Pick angle is another factor. Do we hit the strings with the flat surface of the pick, or do we cut across the strings in a more slanted motion?

Again there's a question of resistance here. Angling the pick slightly, holding it more towards the nub or point, can make a significant difference in how fast and cleanly we can play. And of course, we can switch that angle in the moment depending on whether we're focusing purely on speed or tone.

Holding the Pick

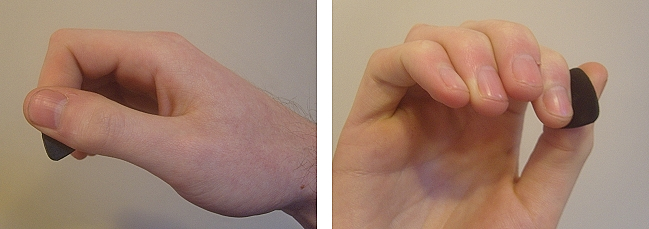

If you really want to go back to basics, even how we hold the pick, between our thumb and finger and how far around we curl that finger in line with the thumb, can make a difference.

There is a holding method that is more like a fist...

One that is more like creating an O shape...

And one where we pinch the pick between the flat tips of finger and thumb...

Three core methods - the fist, O and pinch method. And each one has slight variations that overlap with another. Some players even find using their middle finger against the thumb to be more comfortable.

Final Notes

So there's a lot of room for experimentation, if you're willing to put in the time. That, combined with the incremental BPM process, can be the difference in how long you spend behind a brick wall.

What I think guitar teachers need to embrace more is that technique is incredibly varied and subjective. It has to be a process of elimination, rather than "this is the way". We're all built differently and that includes how our individual motor system interacts with the unique physical construction of our body.

But my overall message here is that, where you find yourself frustrated and feeling like there's an impenetrable brick wall in front of you, just know there are processes and minor changes you can make that can take that wall down brick by brick.

The real challenge here is not in playing what you want to play, rather the discipline of patient experimentation and applied persistence.

It's also worth adding as a final note, that just 30 minutes per day with this stuff is far more effective than several hours at the weekend and nothing in between. Frequent consistency is key.